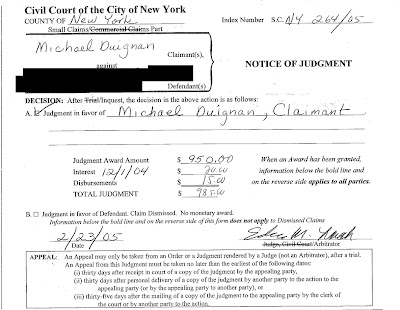

A Guide To Small Claims Court-- By MichaelDuignan - 24 Feb 2010Using the court to right a wrong"As a litigant, I should dread a lawsuit beyond almost anything short of sickness and death." - J. Learned Hand I have been party to a civil lawsuit only once. Though the stakes were insignificant, and the venue as plebeian as one can find in Manhattan, the experience affirmed that judicial outcomes can have more to do with the parties to the suit than the facts or the law as applied to them.A case of personal indignationSix years ago, I moved to New York to start a life after college. With haste, I secured a sublease in Brooklyn until I could afford my own lease in Manhattan. Three months later, I found a flat, and gave my sublessor notice of my departure. I expected the return of the security deposit I had paid upon moving in. When moving day came, she explained that she would only be able to reimburse half of my deposit. She assured me the other half would come soon. As we had become friends during my stay there, I trusted her to repay me and moved on. A year later, I was still without the money. I was amazed at the efficacy with which she had dodged my requests. I did manage to corner her once, offering her a monthly payment plan to draw down her debt, but after a single payment, she again disappeared. I almost let her get away with it too; my parents had each run their own businesses, and I empathized with the fact that she was a small-business owner of modest means. However, once I learned she had taken in sublessees after me who each had their deposits reimbursed in full, any empathy quickly turned to antipathy.Filing with the courtI took the train to the Centre Street Courthouse during a lunch break. Three hours and $15 later, I was set to reappear at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, February 23, 2005 in the Small Claims Part of the Civil Court of the City of New York (not far from where we met Robinson and his musings on "civilization's pathology"). I remember thinking how convenient the scheduling was -- I could leave directly from the office, and would arrive to court already wearing a suit.Preparing for a showdownI decided not to enlist the aid of a lawyer. For one, I sought damages under $1000, and didn't want transaction costs to cut into my winnings. As well, I felt the facts were in my favor. I had a record of sublease documents, cell phone statements, and emails to prove the defendant had wrongfully skirted her obligation to repay. I didn't bother to look into the nuances of tenancy law. Though I wasn't aware of it at the time, my position largely rested on notions of promissory estoppel (yet NY tenancy law was also in my favor). But, something else gave me the calm assurance that I would obtain the outcome I desired.Every case has a turning pointOn the evening of my case, I showed up to court; alas, the defendant did not. Sat before a plain-clothed magistrate, I was given about a minute to air my grievance before he cut me off to rule on account of the defendant's absence. And, like that, I had a certified default judgment in my hands.

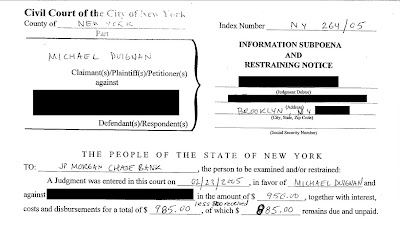

Using the court as a means to an endWeeks later, I walked into a midtown branch of the defendant's bank and handed over an information subpoena. That same day, I received a call from the bank stating the defendant had arrived to pay over the damages, which would remove the freeze they had since placed on her account. I was astonished. What I couldn't accomplish in a year I was able to do in mere hours thanks to the backing of the civil court.

A lawyer's ability to promote efficient outcomesYears later, I question the wisdom of my actions. For any charity I was prepared to extend to the defendant before filing, by enforcing the judgment through her bank, I may have actually done her small business harm. Whether or not this had a material impact on her credit rating, it no doubt reflects poorly to be called in by your account manager to settle a judgment levied against your business. What effect this had on her ability to obtain a commercial loan or line of credit thereafter, I will never know. While I like to think Holmes and Cohen would approve of my pre-hearing strategy, I imagine that they and Robinson would probably look down on my execution of relief. I wasted time and effort by going to court and could have likely recovered my deposit sooner and at a lesser cost to all parties. For one, I could have gone to her location after the hearing and threatened to take the judgment to the bank. I would have thereby recovered damages and she would have retained her standing before her lender. Or I could have sought an out-of-court settlement prior to the hearing, saving me time and effort and her the humiliation of not having appeared before the court.A lawyer's obligation to mitigate the variable of the partiesMy legal victory was largely the result of imbalances in linguistic ability and cultural familiarity between parties, tilted in my favor. I think my pro se experience underscores an important purpose lawyers serve -- to level one corner of the playing field so clients have a fighting chance before they enter the courtroom (or better yet, so they don't have to enter the courtroom). If either of us had contacted one, maybe we could have saved ourselves both time and trouble.I'm surprised at your conclusion. You appear to have sued on your debt to judgment, levied execution and collected the whole sum in about the shortest time possible, with little friction of any kind and no overhead. How you could have saved either time or money by consulting and paying counsel I do not see at all. Nor do I see why you feel that you were too hard on the defendant. She had plenty of opportunity to do right by you before you sued. Tenant security deposits are special objections of legal solicitude, and they nonetheless are a disproportionate contributor to the societal dispute level. Your concern for her relationship to her bank is misplaced. In the first place, unless she is a much larger small business than you let on, her chances of actually having a "lender" rather than just a place where she keeps a bank account are small. Below $2 million/year in gross sales, even small business credit cards, let alone small business lines of credit, are simply not available. Liens are an administrative annoyance for banks, which is why they tend to over-respond and force the account-holder to straighten it out by freezing the account. But you won't have caused them to call her loans. Yes, the language barrier had something to do with why she defaulted, in all probability, but she does business in the city on limited English, and she could have managed in court, too. I think the most promising line of revision is to look more deeply into your own ambivalence about your actions. Intuition tells me that's where something interesting is to be found. |

|